Prologue: the View in 2014

FROM THE HEIGHTS OF GOWAN IN 2014, YOU CAN STILL SEE THE NARROWS—though on a hazy day you have to squint a little—past the trains at Broadway Junction, beyond the Kings County Hospital Center, past where the British camped at Flatlands,

View from “Beacon Hill,” 2014. (photo by author)

Enhanced zoom, view from Beacon Hill, 2014. (photo by author)

and—if you close your eyes—you might be able to imagine that view as an open plain, interrupted only by the occasional farmhouse.

On this date in 1776, as one looked southwest from the Heights of Gowan—the highest point in Brooklyn, the edge of the terminal moraine—things appeared secure: the British and Hessian camp was quiet, the white tents rustled in the breeze, and campfires smoldered. In fact, it was all show, because no one was there.

* * *

Tuesday

Between midnight and daybreak

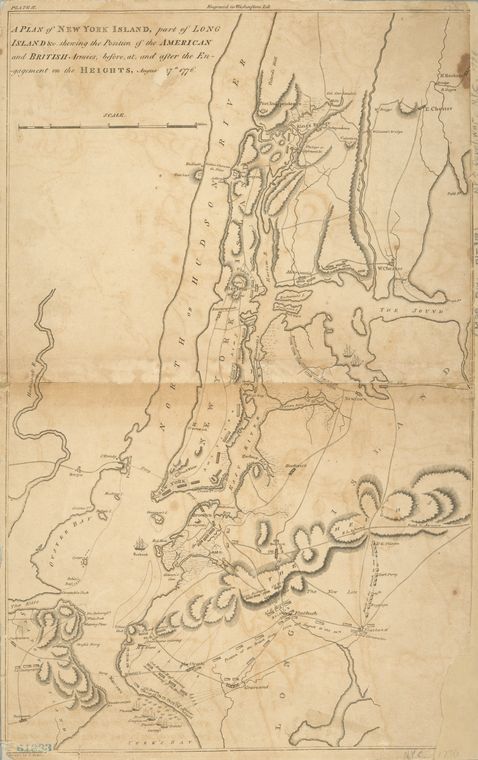

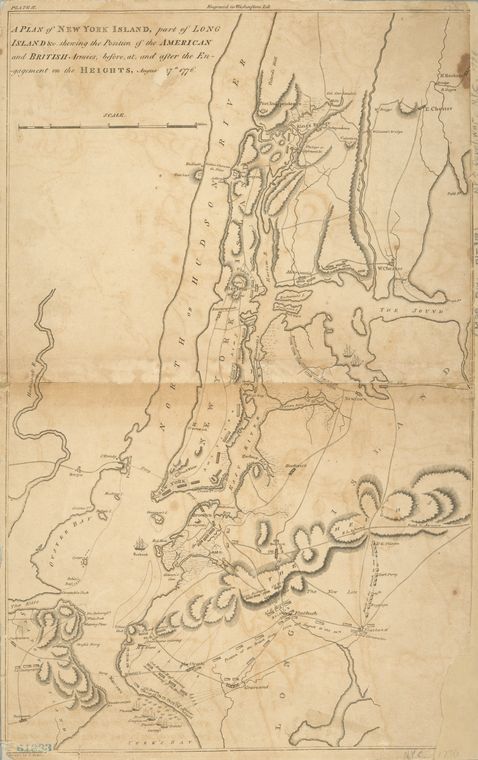

Note the topography! (Samuel Lewis, 1807. NYPL)

OVERNIGHT, A COLUMN OF 10,000 SOLDIERS MARCHED IN A LINE roughly nine miles long, up the King’s Highway from Flatlands to New Lots, turning north towards the Jamaica Pass.

(Jamaica Avenue intersection, 2014. photo by author.)

They moved at a snail’s pace on that unseasonably cool night, led by three local farmers who “knew the way,” stopping roughly every twenty yards so as not to stir attention. At approximately 2:00 AM, the column stopped at Howard’s Tavern (near present-day intersection of Jamaica Avenue and Broadway):

(NYPL)

As McCullough tells it, the armies met little resistance at the Tavern (there may have been some life/limb threatening), so the column pressed on up the hill. Captains William Glanville Evelyn and Oliver DeLancey, Jr., rode forward to the Rockaway Footpath, a “winding, rocky road through a narrow gorge overhung by trees and little wider than a bridle path,” which marked the opening of the Jamaica Pass:

(2014. photo by author)

Five Americans were stationed guard at the top of the footpath, and—by some accounts—the startled (and probably tired) sentries simply fell in with the British officers and were summarily captured. (The commemorative marker, below, is slightly inaccurate, nonetheless.)

(2014. photo by author)

It took nearly two hours for those thousands of men to march through the pass. At first light, all assembled on the Bedford Road, they were ordered to rest in the tall grass. It was approximately 6:00 AM.

* * *

9:00 AM

IT WAS A BEAUTIFUL MORNING, WHEN TWO CANNON BLASTS MADE SIGNAL to the Hessians and General Grant that it was time to commence their assaults. At 9:00 AM, Howe’s army pressed on toward the village of Bedford, but Grant had already decided to occupy the attention of the Americans [at the Gowanus Road] ahead of schedule,” a move which rousted General Putnam out of bed at the Brooklyn headquarters at three in the morning. Putnam and General Samuel Parsons rushed to the “front lines”—in this case, the fortifications—not knowing that a larger force still advanced behind them.

Near present-day Brooklyn’s intersection of Fourth Avenue and 35th Street (and the 36 Street subway station entrance),

(2014. photo by author.)

Grant and his 300 troops surprised the Americans on guard, many of whom fled immediately.

(NYPL)

Near the Red Lion Inn (at the junction of the Martense Lane, the Narrows Road, and the Gowanus Road), Grant pushed ahead down the Gowanus Road toward Brooklyn Heights, driving the Americans back toward their fortifications for nearly six hours.

* * *

On the American side, General Stirling and his 1,600 men (including Huntington’s Connecticut regiment, Atlee’s Pennsylvania battalion, Smallwood’s Marylanders, and Haslet’s Delaware battalion) “fought valiantly,” and Parsons’ troops held the line through two assaults on the higher ground, near “Battle Pass” in today’s Green-Wood Cemetery:

(NYPL)

(2014. photo by author.)

and fighting also commenced at “Battle Pass” (more on that duplicitous naming later) in modern-day Prospect Park, as Howe’s line of thousands progressed.

That was only the beginning, of course. While Grant, Parsons, and Stirling skirmished, andHessians bombarded Sullivan’s troops, three of General vonHeister’s brigades stood in a mile-long line, waiting to move, on Flatbush Road—a third line of attack.

WASHINGTON HAD LANDED AT BROOKLYN THAT MORNING, and proceeded directly to the fortifications near Brooklyn Heights—what were known as the “Brooklyn lines,” i.e., the border of the village—some two miles away from the two fields of battle. He had probably heard the signal cannons blare as his boat approached the Long Island shore. Glancing south when he crossed the Sound (East) River, Washington also might have observed five British warships beginning their advance upriver, heading toward Kips Bay and taking advantage of favorable winds at their backs. These were not good signals.

* * *

LINES OF ATTACK:

(William Faden, 1776. NYPL)

Central line of attack: Battle Pass (Between Brooklyn and Flatbush) (not to be confused with the fabricated path in Green-Wood Cemetery of the same name)

(NYPL)

In the thick woods of the ridge separating the towns of Brooklyn and Flatbush, a small advance guard tried their best, on that hot day in 1776, to hold off the thousands of Hessians. But, after felling a landmark, the Dongan Oak,

(2013. photos by author)

(2013. photos by author)

the Americans “had time to get off only a shot or two, or none at all.” In today’s Prospect Park, the East Drive runs along much of what was once this legendary path.

(2013. photo by author.)

Three markers are the only clue that anything happened there at all, and most parkgoers pass them by unnoticed. Even one of Prospect Park’s interns, writing for the Alliance’s blog on the Battle’s anniversary got the location wrong.

(2013. photo by author.)

(2013. photo by author.)

(As if on cue, when I photographed the Battle Pass marker, two teenage girls remarked after reading the plaque, “Yep, we never learned that in U. S. History!” Take that, Common Core?)

* * *

In 1776, vonHeister claimed that the Continental soldiers “surrendered immediately and begged on their knees for their lives,” but in 2013, the view (below) both up and down the Drive was dark, even minus the smoke of gunfire and haze of war.

(2013. photo by author.)

(2013. photo by author.)

Perhaps some men simply feared what they could not see. If they ran from the woods, those who made it out were greeted by British gunfire. These were “terrible hills,” indeed.

Southern line of attack: Vechte-Cortelyou/”Old Stone” House (Village of Gowanus)

(2014. photo by author.)

Just southwest of Battle Pass, by 11:00 that morning, Stirling’s hold proved ephemeral. Barreling down from the ridge, thousands of Hessians struck on one side, and more British pressed forward at Gowanus Road behind the Americans. Near present-day Fourth Avenue and Third Street, an old Dutch farmhouse (now reconstructed, and called the “Old Stone House,” above) became central to the field of battle.

(Brooklyn Historical Society)

Surrounded, Stirling ordered his men to retreat across Gowanus Creek, while he and a few hundred Marylanders held the line. As Stirling and company struck the enemy five times, desperate men waded across the Creek,

(NYPL)

some got stuck in the mud, and those who couldn’t swim either drowned or were taken prisoner.

* * *

Washington never made it to the actual battlefield. Watching the debacle from a safe distance, near the present-day intersection of Court Street and Atlantic Avenue:

(2013. photo by author.)

he declared, “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose!” Depending on who one asks, even now, that quote was either the most heartfelt expression of admiration, or the eighteenth-century equivalent of “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job“—an oblivious compliment at a time of extreme catastrophe.

* * *

Evening

At day’s end, both the village of Gowanus and the town of Flatbush were smoldering battlefields, and hundreds of men on both sides were wounded. Estimates now provide that in those few hours—between approximately 3:00 AM and noon—300 Americans were killed and 1,000 were taken prisoner. Counting the Royal Navy, over 40,000 men participated in the “skirmishes” that day.

40,000 people is a few souls fewer than the entire population of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and seven thousand fewer than all of the participants in 2011’s New York City marathon. (For a visual, consider what it looks like when the marathoners Fourth Avenue—a modern-day road that follows the same path on which the British advanced, the Gowanus Road—in this image.)

IT WAS ALL OVER in six hours, more or less. General Grant wrote to a compatriot, “You will be glad that we have had the field day I talked of in my last letter. If a good bleeding can bring those Bible-faced Yankees to their senses, the fever of independency should soon abate.”

Even two centuries removed, debate continues as to the ferocity of the battle, its participants, and the aftermath. Local historians advocate that a vacant lot must be consecrated as hallowed ground, but McCullough implies that that argument is flawed: “there was no truth to an account in a London paper of Hessians burying five hundred American bodies in a single pit.”

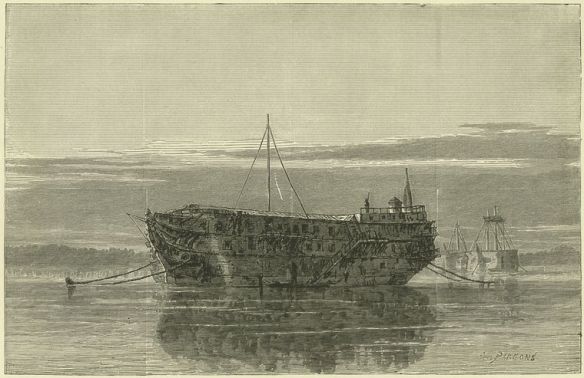

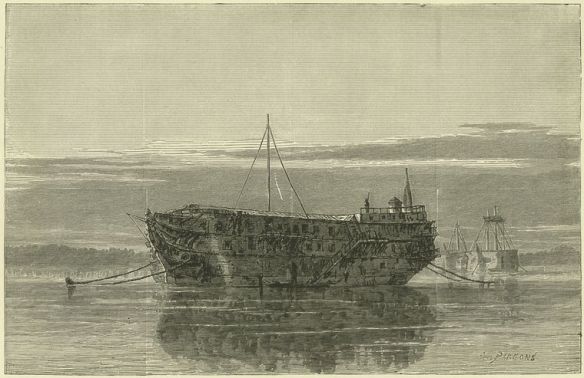

In the evening hours of August 27, 1776, the true horrors had just begun for many of the battles’ survivors. For some, their future lay in confinement on “prison ships,” like the notorious HMS Jersey (below),

(NYPL)

soon to be moored in Wallabout Bay.

The guns momentarily silenced, “pitiful cries could be heard from wounded men who lay among the unburied dead in the battlefield.” A cold wind blew in from the north that night. Things had changed, not just on Long Island, and the fate of a new nation was at stake. The Battle of Long Island was the first major battle after the Declaration of Independence, and it was also a major loss.

(2013. photos by author)

(2013. photos by author)

You must be logged in to post a comment.